Ka-Chun Lo, Associate in Quantitative Research, MainStreet Partners

All actions have mixed potential outcomes, both positive and negative. This is at the heart of potentially the most challenging element of Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR): wealth managers, financial advisers and other financial market participants’ need to report Principal Adverse Impact Indicators’Principle Adverse Impact’ (PAI) indicators are mandatory indicators and metrics that aim to show the potential sustainability risks of certain investments.

The PAI regime came into force from April 2022, but investment managers and advisers were meant to publish reports using the PAI specific template by the 30 June 2023.

Are fund managers adhering to PAI?

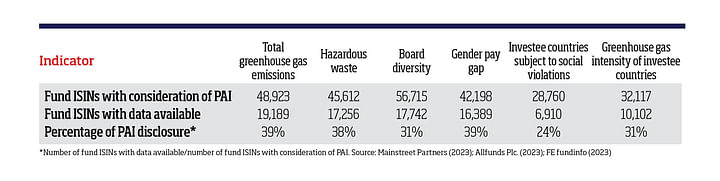

MainStreet Partners has analysed the European ESG Templates (EET) as of the beginning of June 2023 with a sample of 157,487 unique fund ISINs, and found that more than 40,000 funds claim considerations of the four selected mandatory corporate PAIs (total greenhouse gas emissions, hazardous waste, board diversity and gender pay gap); however, around 35% disclose information across these PAIs.

Two additional mandatory PAIs apply to investments in sovereigns and supranationals: investee countries subject to social violations and greenhouse gas intensity of investee countries. For these PAIs, 24% and 31% of funds respectively disclose information. So, while many EET funds claim they consider PAIs, there is a lack of pervasive evidence for supporting such claims conclusively, as can be seen in the table.

PAI disclosures for selected mandatory PAIs

Under the SFDR, financial market participants can choose to publish a PAI statement on their website explaining why they do not adhere to PAI reporting requirements.

Under the SFDR, financial market participants can choose to publish a PAI statement on their website explaining why they do not adhere to PAI reporting requirements.

Fund managers: What is in it for them?

Why should asset managers consider going beyond mere regulatory compliance with PAI reporting?

Our view is that doing so can bring about a multitude of benefits for asset managers.They not only showcase their compliance with regulations but also demonstrate their dedication to managing the adverse social and environmental impacts of their investments. The adverse impact management and transparent disclosure can enhance their public image and, most importantly, foster trust among their clients. Reporting on mandatory and optional PAIs create a win-win situation for investors and asset managers.

On the one hand, investors gain access to a broader range of information, enabling them to make more informed investment decisions. They can evaluate the environmental and social aspects of the investments, aligning their preferences and needs with asset managers who actively manage these impacts. On the other hand, asset managers can better cater to the diverse ESG preferences of investors and develop distinct comparative advantages that set them apart from their peers in the industry. The PAI reporting fosters transparency, trust, and alignment of interests between investors and asset managers. It’s about trust, reducing information asymmetry and developing comparative advantage for fund managers.

Company/stock-level reporting

For fund managers to accurately report on PAI, they need to gain the relevant ESG data from their stock holdings. This currently poses a significant obstacle because only a small proportion of corporates today report on hazardous waste data or gender pay gap information.

One way we have found to address this challenge is to leverage machine learning and advanced statistical estimation models to fill these data gaps effectively, when we possess a high quality of reported data as input and a strong level of statistical confidence. Choosing a third-party data provider with strong relationships with a wide spectrum of data providers and a highly skilled in-house research team allows asset managers to gain a deeper understanding of the missing puzzle pieces. From that, they can make more informed decisions on their PAI requirements.

Another challenge for investors is the potential for variance in data provided by different data providers. For example, if data provider A reports 100 total greenhouse gas emissions for a company, and data provider B shows 1,000 for the same company, which figures should be used and reported on? We have found the difference in data from providers can be 10-50%.

It requires a lot of effort to engage with this large amount of new data, understand the methodologies, check the quality and choose the most accurate and reliable figures in order to minimising this pain points and establishing robust assurance processes around the PAI data used.